All Civilizations Need a Great Romance

A grand and long-stretching civilizational canon which that civilization's ruling elites find themselves irrationally in love with and will forsake all other desires to fulfill and embody.

Raise a child on tales of chivalry and dragons, and he will want to grow up to be a knight. Raise a child on stories of exploration and adventure, and he will want to grow up to be a pioneer. Raise a child on nihilism or sexual debauchery, and he will grow up to be a nihilist and a gay sex pest.

It is literally a life-and-death situation when you choose what kind of story you want your descendants to be raised on. And all of our ancestors knew this when they created blasphemy laws, literally killed people who would attempt to undermine the stories that their civilizations were built upon, and propagate those same stories over and over again, to re-invigorate the next generation.

Such as the Christians throughout the centuries, treating blasphemy as a death-worthy crime, not because God Eternal needs protection, but because blasphemy murders the souls of our neighbors, especially the ones committing blasphemy.

“The Romance of the Three Kingdoms” is a great example of what happens if a civilization elevates a specific piece of literary work and seduces its ruling class with tales of great and virtuous heroes who earn the respect of their people and the immortal echoing of their names throughout the great halls of men. Standing as a pinnacle of literature, immortalizing historical figures from China’s Three Kingdoms Era as near-mythical icons in Chinese culture. Told and retold through operas, movies, TV shows, and video games, these characters have ascended to demigod status, exerting a profound influence on the psycho-cultural development of Chinese society.

And not just limited to Chinese society, but all throughout the Sinosphere.

Takenaka Shigeharu (竹中 重治) was styled by the people of Japan during his time as the Zhu Ge Liang (诸葛亮) of his time, because he himself wanted to emulate the virtues and intellectual prowess of the man. A Japanese samurai prominent during the tumultuous Sengoku period (戦国時代) of the 16th century, he held the position of castle lord at Bodaiyama Castle, serving as a key strategist and adviser to Toyotomi Hideyoshi (豊臣 秀吉).

Gwanggaeto the Great (廣開土大王) was a renowned king of Goguryeo (高句麗), one of the Three Kingdoms of Korea. The legacy of Liu Bei (劉備) most befits him as they shared the same traits of being a virtuous and benevolent ruler, which Gwanggaeto strived to emulate.

Ngô Quyền (吳權) was a Vietnamese general who played a crucial role in the defense of Vietnam against Chinese Southern Han invaders in the 10th century. He can be compared to Sun Jian (孫堅), when Ngô Quyền’s ingenious victory at the Battle of Bạch Đằng River (白藤江) ended over a thousand years of Chinese rule over Vietnam.

And there are so many more historical figures deeply moved by the story’s transformative power, akin to those of a religious nature. Powerful narratives like this have completely reshaped an entire people’s psyche, significantly redirecting the course of an entire civilization for millennia after their creation, texts which still exert a profound influence on societies worldwide.

When I watched Liu Bei (刘备), Guan Yu (关羽), and Zhang Fei (张飞) swore that oath of eternal and unbreakable brotherhood, my heart was ignited with the desire to find like-minded men after my own heart and perform our own oath in a peach garden.

When I see millions and millions of invading migrant hordes break into the country without regard for the sanctity and the posterity of the men who built up the land they so desperate crave for themselves—and still have the gall to brag that without them, the country would be nothing—I am reminded of Cao Cao (曹操) murdering his father’s sworn brother, Lü Bo She (呂伯奢) and the entire Lü household after Boshe offered Cao Cao refuge.

At least when Cao Cao murdered his uncle and his household, he thought he was getting betrayed when he heard the sharpening of knives; these ingrates openly and proudly stab their gracious hosts and then rub it in with the rhetoric that the host nation needs them to make the country better, how it’s a dying country without them because the population is so low and birth rates are declining and the kinfolk who have created this nation aren’t ambitious enough to fill the high level jobs.

The hearts of men are not stirred by statistics or talking points on a presentation slide. Never once did I explode into a fiery anger by a line on a graph showing that throughout their entire lives in Denmark, immigrants from the Middle East, North Africa, Pakistan, or Turkey have never become net-contributors to the public purse. Never once did I collapse in overwhelming happiness to see the charting line of the Dow Jones Industrial Average going up on a graph.

My fire is kindled to learn the Son of God, the Conquering King, suffered grievously and died willingly so He may offer amnesty for all my sins. My mind is filled with fantasies of how may I repay this kindness and undeserved mercy, how I shall vanquish His foes and save His flock. And my heart is ready for anything He needs me to do: a time to plant and a time to uproot, a time to kill and a time to heal, a time to tear and a time to mend, a time to love and a time to hate, a time for war and a time for peace. (Ecclesiastes 3)

My fire forge forth an iron sword so I may vow it to the Iron Lord.

Good lords deserve good vassals, and good vassals deserve good lords. As Guan Yu himself stated when he swore that oath of brotherhood: “A good bird chooses a good tree to perch upon, and a good man chooses a worthy lord to serve.”

Tales like these do far more than any think-tank sitting around discussing trivial matters or another podcast being started by a man you like to hear from. A three-minute scene of King Alfonso bursting into remorse and anguish for all the wrongs he has done to El Cid is more hard-hitting than another two hour long discussion on a podcast—not that podcasts don’t have its uses, of course.

“I am king of nothing! No king at all! I will make myself a king! I will!”

Our fathers knew what we had forgotten.

The West used to rely upon three sources of mythology: the classical, which encompassed ancient Greek and Roman tales, the French, and the English traditions. Among these, the ancient Greek and Roman mythology holds the most significant influence as it is the earliest and oldest. Many stories from this tradition endured, partly because Latin was the international language until the 1900s, when French gradually took over for a brief time.

Latin education often centered around texts like Virgil’s Aeneid, an epic poem recounting the journey of Aeneas, the last survivor of the Trojan War from the Trojan side, who fled to Italy and laid the groundwork for Roman civilization. Students enamored with such adventures would delve into additional epics like the Iliad and the Odyssey, introducing them to heroes like Achilles, Odysseus, Hercules, as well as Jason and the Argonauts.

Unfortunately, the revival of Norse mythology during the 20th Century contributed to the decline of Greek and Roman mythology, pushed by German intellectuals and prompted themselves to reject the latter due to its association with rationality and philosophy, perceived as too structured. This rejection resonates with contemporary movements seeking to set aside rationality for dynamic, unfettered creativity. Norse mythology, with its emphasis on dynamism over rationality, gained prominence, reshaping the civilization’s romance.

Then there was the French, epitomized by Charlemagne and his paladins, offered tales of enduring virtue and unabashed heroism, of pure hearts and sincere faith. The reason why the romantic historic account of Charlemagne lived for so long was because he fought the Saracens. He and his paladins, all of their adventures are derived from the Mandate of Heaven which appointed them as the heroes. They were absolutely on the side of all that was good and right, and the Saracens were serving a blaspheming heretic in the control of Satan.

When French soldiers marched on the order of their king to secure the realm and be the sword and shield of Christendom, they marched singing the Song of Roland, mourning how black was the day he died. His great name shall live in song wherever brave men take up arms to right a grievous wrong. Roland, the noblest of all the knights of Charlemagne.

Then, as tensions between England and France grew in the early modern period, the Carolingian historical myth was put aside in the Anglosphere. Charlemagne, considered to be the Father of Europe and yet also the forefather of the French nation, became a symbol of animosity for the English, who historically viewed France as their greatest nemesis. France was England’s archenemy until the beginning of the 20th Century, when Germany dethroned France as the target of English ire.

English hatred for France led to smear campaigns against French history, particularly regarding the Crusades, perpetuated through English historiography. However, contemporary re-evaluation of historical sources reveals these narratives as false propaganda rather than accurate accounts. This distortion of history hindered the English from relating to Charlemagne’s legacy.

In contrast, the English cycle, epitomized by the tales of King Arthur and the Knights of the Round Table, became deeply ingrained in English-speaking culture. King Arthur, serving as a counterpoint to Charlemagne, emerged as a cultural icon in response to French martial chants like the Song of Roland, which galvanized French warriors against the English. The English, seeking a comparable mythos, turned to their own history, crafting the legend of King Arthur as a unifying narrative. Thus, King Arthur’s myth bore a symbolic connection to the Charlemagne tradition while distinctly shaping English cultural identity.

I have no doubt that any English-speaker living in a nation of the Anglo-Saxon tradition is familiar with King Arthur, even the most mythologically illiterate ones.

Even the Americans, whose founding beliefs sacrificed the prospect of a formal ruling class, recognized that aristocracy was in man’s nature, both inevitable and beneficial for their attempt to preserve the way of life they fought to keep. Outstanding bloodlines were the backbone of colonial society, building churches, schools, brotherhoods that were essential.

And to guarantee this continuation of their aristocracies covering many fields such as politics, military, economy, and religion, they filled their inheritors with grand stories of their great forefathers and passed down their knowledge, duties, and seats. And knowing that their authority was not derived from noble titles by birth, they were desperate to prove their noble lineage and their worthiness to lead through meritorious deeds, strind after strind, else they must put themselves out of the way for better men who can serve as guides.

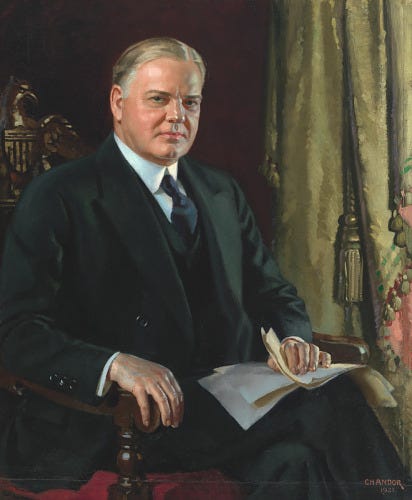

Hebert Hoover is one such great example. Before he became President, Herbert Hoover was a undoubtedly a proven man, feeding Belgium during the First World War, providing aid and debt relief all over Europe after the fighting had let-up, famously worked to relieve the Volga Famine of the early 1920s. All without the expectation of any great, earthy reward. A lowly boy born to a Quaker family in a cottage in Iowa becomes a self-made multimillionaire, then President. An apt and prime of the quality of man Americans were back in those days.

Then there’s Dr. Joseph Eastman Sheehan, an American plastic surgeon whose clients were metropolitan stars. His heart was stirred by the plight of the Spanish Nationalists during the Spanish Civil War and volunteered to do free surgeries. The man was wealthy and has everything he’s ever wanted. Top of his field, in perfect safety. He had no legal obligation to help the Nationalists, yet he goes out and helps wounded soldiers, who would otherwise never have normal lives again, with specialized treatment that they couldn’t get from anyone else.

Both of these competent men were in love with the romance of his civilization: “But lay up for yourselves treasures in heaven, where neither moth nor rust doth consume, and where thieves do not break through nor steal: for where thy treasure is, there will thy heart be also.” — Matthew 6:20-21

It is no accident that arguably the greatest Americans emerged from this informal aristocracy. They were nurtured for greatness, deliberately inspired to emulate the heroic figures and societies of the past.

A great romance.

Just as Napoleon, who modeled himself after Charlemagne, who modeled himself after Augustus, who modeled himself after Alexander the Great, who modeled himself after the fictional Achilles.

The Disastrous Chance Noir

Andreus Lyon had long been an admirer of his father, and his father before him, and so on. He loved the stories his mother told to him in his childhood before she passed away. Stories of knights and kings, of honor and chivalry, a time where the world was enchanted with the souls of societies. Stories of Roland, the Prefect of the Breton March, of how he bravely stood his last stand.

Yet Andreus does not live in those times. He lives in modern Paris, a city gone to ruins. A place whose people does not share his veneration of the old culture and its old glory. And he has no chance to prove himself to be someone who could live up to the dignity of his forefathers.

Until chance happened and bestowed upon him a mysterious ring that can enhance his physical capabilities. His strength became equal to ten men, his foot as light as a feather, and his eyes as sharp as the owl or the cat hunting prey in the night.

And when he met a certain baxter who has been terrorized by the local gang, this was his chance to prove himself that he would've been just as noble and brave as Roland.

Worth of an Englishman

Available now on Amazon:

Britain is on the edge. For decades, the looming threat of unbridled chaos long hangs over the azure main. Every other day, there is always some attack that riles the factions of the country up in civil unrest, adding racial tensions that have created a powder keg, long simmering beneath the surface, and explode it out into open conflict. Desperate to maintain control, the government has employed widespread media campaigns aimed at pacifying the masses. Yet these measures only seem to deepen resentment, especially with one Carlun Britenwielder.

Andreus Lyon had gone back to the normal life, seeing anything outside of it as a fool's errand, until a vision from the Beyond commanded him to go to England and employ his skills once more. If he should return to his civilian life, then at the very least, he should teach and leave behind someone who has an even stronger will than Andreus had.

But the last time Andreus did something with good intentions, it ended badly for him. This time, the consequences are going to be much bigger than just him and every matter of his life. Would this endeavor finally give Andreus the rest he longs for, or will he have created an absolute monster whose bloodlust is unending?

ADDENDUM:

YouTube Autoplay introduced to me something amazing.

There are still children to this day, taught to recite a poem almost two thousand years old. “On the White Horse” (白马篇) was a poem written in 196-220 A.D. by a scion of Cao Cao, Cao Zhi (曹植), considered to be one of the greatest poets in the history of China, and heir-apparent to the Wei State (魏国) until his brother Cao Pi (曹丕) politically out-maneuvered him.

And here is a government-sponsored choir singing the poem:

And here’s a pop-idol singing the same song on national TV:

When’s the last time you’ve ever seen a celebrity singing a culture heritage this old instead of songs about sex, relationships, and other personal problems?

The oldest poem or song I could think of which rivals this Chinese poem’s age and still somewhat relevant is “Veni Veni Emmanuel” written in the 8th or 9th century, still hundreds of years after Cao Zhi wrote this piece.

Anyway, here’s one with English subtitles:

I just thought this kind of cultural continuity was neat, but I’ve already written and structured this article the way it was and adding this information into anywhere in this article would break the flow, so I’m just adding it here.

I must confess to appreciating the vote in favour de la mythologie and great Matter de France, but if I may say so; I'm quite a bit fonder of the Norse tales than the Greek on account of the themes of duty, honour and courage. The Greeks have their virtue, but I think a balance of the two is best.

Though, my own stories specifically those of Olympnomachi and others are about restoring the old myths and ideals and ideas. But really, this is the finest essay on the importance of romance and myth I have seen thus far kudos.

You underestimate King Arthur. There are chivalric romances featuring his knights all over Europe. There are even versions written in Hebrew.

Even the French took readily to his tales, partly because there were many powerful people who were descended from the real people in the Matter of France, and many others who claimed it -- from real and fictious characters.